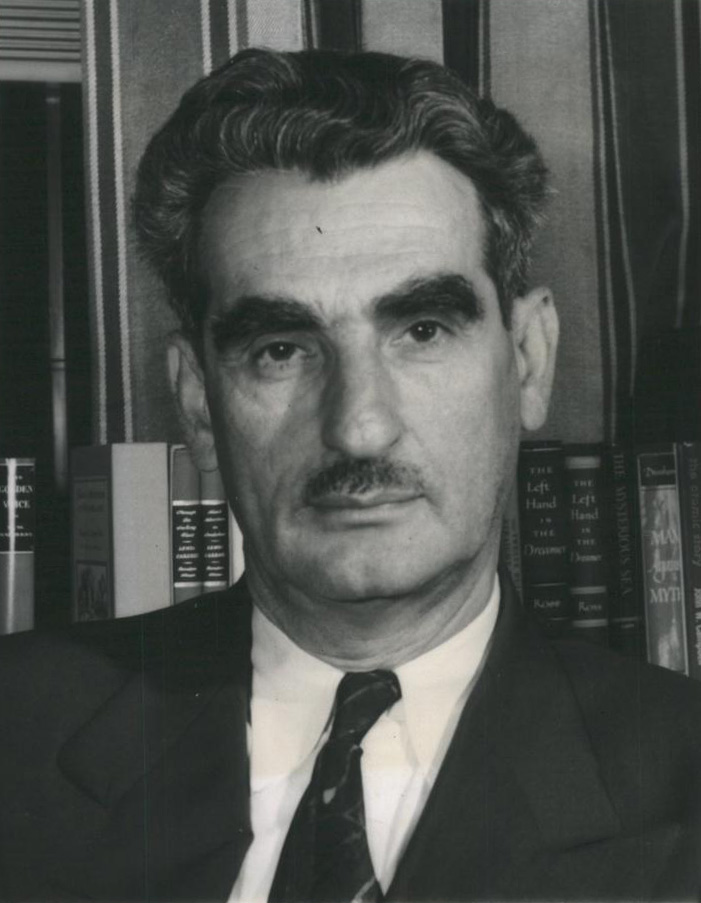

In the book “Symphony of the Jewish Tree of the Brest Region” by Vladimir Glazov (2019), among the wide life stories of the great and famous names of those who were born in Brest and its environs, there is just a small biographical essay about Joseph Aaron Margolies. Though, due to his professional activities, he was a rather public person, information about him is scarce and laconic. Just where he was born, worked, died. There is much more information about his son-in-law and grandson. The son-in-law, Leo Rifkin, is widely known in American theatre and cinema circles as the scriptwriter of the most popular TV series (The Addams Family, The New Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, etc.). His grandson became famous thanks to his work as an art director of the rock band Grateful Dead.

But one thing is clear, the son of a poor Jewish blacksmith from Brest-Litovsk, Joseph Aaron Margolies, managed to live a good and interesting life and he takes an honourable place among those, whom Brest can be proud of.

Joseph Aaron Margolis was born on December 25, 1889 in Brest-Litovsk. He was 12 years old when his family left for New York, America. Where and what he studied his biography does not mention, but we know for sure that at the age of 16 he began working as a library assistant at the Rand School of Social Sciences in New York.

“This library was founded by followers of the US Socialist Party, who considered comprehensive education of workers as one of their main objectives. Apparently, Joseph himself learned a lot during his six years work in the library. In 1912, he was employed in one of the largest bookstores in New York – Brentano’s, located on Manhattan’s famous Fifth Avenue. In the late 1920s, Joseph Margolies left the bookstore to become a commercial director of the Covici-Friede publishing house. However, the publishing house, on existing for about ten years, went bankrupt in 1938 and Margolies returned to the Brentano’s bookstore, which became almost his own. From 1944 to 1947, he was a director of the Council of this bookselling house, and in 1945-46, Margolies was the President of the American Booksellers Association. From 1955 until his retirement in 1960, Joseph Margolies was a manager of the Center for International Book Trade Affairs in the Foreign Policy Association and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace” (Vladimir Glazov “Symphony of the Jewish Tree of the Brest Region”, p.84)

Joseph Aaron Margolies has definitely played a significant role in the development of the American book selling business. He died being a very old man, aged 92. He bequeathed his archive, comprising unique photographs, correspondence with prominent people of that time, documents, manuscripts, to the library of Columbia University.

Joseph Aaron Margolies took part in the Oral History Project. He was interviewed twice. The first interview in 1971 dealt with his professional activities. But 6 years later, in 1977, journalist Clifford Chanin asked Margolis to talk about his childhood in Brest-Litovsk. This interview was recorded on tape, that was presented to the William E. Wiener Oral Historical Library of the American Jewish Committee. Today this recording is held by the New York Public Library. The old man in it vividly and in detail describes, how Brest-Litovsk lived at the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, that city no longer exists, as well as the people who lived in it, but they left us some memories, helping us get to know the history of our native Brest.

Brest-Litovsk. View of the residencial buildings on the New Boulevard. In the distance you can see the intersection with Shirokaya Street.

House

I was born in Brest-Litovsk. It was quite a big city. It must have looked much bigger than it really was to me as a child. But I remember perhaps forty-five thousand out of fifty thousand of the town’s inhabitants were Jews.

We lived in a fairly big building. There was no running water there. The water had to be taken from the well, which was outside a little distance, and brought home. No plumbing of course.

There was a grocery store at the other end of the building, Reb Meyer was his name. Everybody was called “Reb” there, “Rov,” Just as we say “Mr.” here. Most of the women charged, they didn’t have the money till payday. He had a late and he had a queer way of keeping records. He would write on the slate in a sort of a shorthand he had a tally, but my mother, who was a very good mathematician, kept it all in her head, she knew the amount.

There were all sorts of things in the street. I mean it was not very clean, especially the alleys were never clean. I came across that in Naples when I went into the Italian ghetto.

Neighbors came into our house. There were no telephones and no bells on the doors. Neighbor came in, that’s all. And if he came in during dinnertime he would hear, “essen,” which meant “Come eat with us”. But the slogan was “essen. Shainen dank.” So, this was the form, but they came at any time they wanted to come.

We had friends, we had a lot of relatives there too. My father’s sister lived close by, and I used to visit her quite a bit. She had a daughter, a very handsome girl, who was a cigarette maker, and she didn’t work in the factory, she would take the work home and she had a little machine where she would make cigarettes. And I would sit there and watch her, she was so quick doing it, and she would sing during the work.

Making cigarettes. Source: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Apartment

I think the house had several apartments. We had a corner apartment on a street that was called the Breitegasse, Broadway but it was unpaved. It had a ditch, which I saw in Iran even ten, twelve years ago.

I can draw from memory a plan of the apartment. It was a kitchen, a big room, another big room, a dark room with a skylight from the other room, and that’s all. Three families lived there. Eight children had to live there and two parents in the apartment.

Our family lived in the big room. It was the corner room and it had windows to the street. We called the enormous room dining room, living room, bedroom, meaning all the same room. Over the table our family was large. We had a hanging lamp that we could pull up and down, which my father bought. Just as he had a front seat in the synagogue, he wanted this. Neighbors would come in to look at it. They lived in other rooms of the apartment. The next room was separated by an oven which heated the apartment. That was rented to a couple who had no children, and the wife ran a sort of a dressmaking business and my two sisters learned how to sew in that place. In other words, they didn’t have to go out to work, they worked there. This woman’s husband was one of the most remarkable people that I can remember in my childhood. He was a house-painter in summer, but he wrote the Torah in winter on parchment. He had these feather pens, and it was just marvelous. He took me in hand too, because he saw I was interested in what he did, and I would sit there and watch him write the Torah. He was a redheaded man, a charming guy, and he would look up at me as though I was his own child. They had no children.

Next in the dark room the only light they had was from the room where the sewing machines were, so there was a transom — lived a man and his wife and a young son who later went to the army, when he grew up. The man was a big, heavy, hulky man and the kind of a man that’s described in Sholom Aleichem as a am ha-aretz and he was a public carrier. He carried bundles for people, and his wife did the cooking and took care of her son when he was there. And the kitchen was a common kitchen for the three families, a big oven, and each one cooked his own meals. All the families cooked separately and ate separately.

Family in the house near the stove. Photographer Serzhputovsky A.K.

When I listen to the criticism of how the poor people live in Russia now, I’m incensed because there couldn’t be any more crowded living, specially of my family in such crowded conditions. Everyone in my family in one room and then two other families close by. I never felt the closeness really. There were three beds I remember. My brother and I slept in one bed, my two sisters slept in the other bed. Some of us slept on the floor, literally on the floor. In summer it was nice, because we slept outdoors, except on rainy days. In winter we slept four in a bed. Sometimes we had a guest, I don’t know where we put them, in the kitchen probably.

When a young baby is born, you don’t have these cradles that you rock on the floor, I never saw it in Russia at all. Maybe I did, I guess so. But in a crowded place where we lived the cradle is hung from the ceiling, hung by four ropes, so that when the baby begins to cry you begin to swing it, and I’ve seen that in many homes and saw It in my home. My younger brother, who was two years younger, which means that I was four years old, and I remember that well. Whenever the child began to cry my mother would say, “Kinder, Children, swing him,” or “rock him,” and he heard it so often that whenever he began to cry, he himself would say, “Kinder”. Everything was so close, because there were no separate bedrooms for children or anything like that, and this was part of the routine and I remember it so well, that cradle hanging from the ceiling.

The relations between the different families crowded so close together were fine. Excellent. My mother was very diplomatic, and she was very nice, and of course the couple, the man who wrote the Torah, they were superior people, both of them really were very fine people. This of course brings in my childhood. It was a good childhood.

Passover preparations. Source: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Father

My father was a blacksmith. I would say more an ironworker. He was very deft; he could do anything. I used to bring his lunch to him when I was about six years old, and he worked alone with the anvil and the iron that he took out of the fire. It was hot and he would bend it, not with his hands, but he would bend it with pincers so easily that it was just remarkable to me watching him. I never saw him shoe horses and I don’t believe he did, because he was too good a man for that, he was inventive. He taught the people that employed him how to use tools in a certain way that would make things easier and cheaper.

I’m sure he didn’t earn much money. He worked for all Jews. If I remember right, it was about ten dollars a week. This is what I heard. He was religious in this way, that he had a seat in the synagogue, generally right with the big shots, and I remember sitting next to him all the time.

Blacksmith. Source: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Mother

My mother was a very handsome woman. She was one of the wisest women I have ever known, though she was, I would say, Illiterate. She had a love for life, and people would come to her for advice all the time, not only relatives, but friends would come, and she had a very nice way to take people in.

She had to take care of a group of children, they were of various ages. She would send them to work, to cheder or wherever they had to go, make breakfast, dinner for them, she had to go out shopping, wash clothes.

When my father came home, he had to have a good dinner. although he wasn’t that kind who would knock on the table, but she had a good dinner. Yet after dinner of course the girls washed the dishes, they were old enough by that time to do it. She would sit down and knit socks for all the children. This was the hour instead of looking at television, instead of listening to radio, we would all sit there and talk to each other, and my mother had time for all that work, imagine that. So when she came to America, she said, “I don’t understand it, everybody curses all this stuff.”

She was that wise, she was a fine woman. If one of us kids misbehaved, she wouldn’t tell my father about it until he had his dinner. She explained that if I tell him before dinner, he might not enjoy his dinner, and sometimes he’d punish us, but gently. I don’t remember much about being deprived of anything. I remember when my mother told me the story that once I came home from cheder and I opened the cupboard, where the food was and she said, “There’s nothing there.”

Women and children. Photographer Serzhputovsky A.K.

Children

My parents had nine children. There were two brothers and two sisters born before I was born and two brothers and two sisters after I was born. I came in the middle. My youngest brother was born in America, and he went through the usual American kind of thing, he went to a law school. After he graduated, he didn’t become a lawyer. Instead of that he went into theater and particularly in the movie industry.

All the boys, except my youngest brother who was born in America, had double names. My eldest brother was Hersch Yudel, my next brother was Itzik Leib, I came after, and mine was Yosef Aaron. The younger brother, who’s dead now, was Chaim Pinchas. But my youngest brother who was born in America, his name was Abraham. See, it was all practically biblical names.

My eldest brother was a carpenter. When he came to America, he became a teacher and he then became a dentist. The younger brother Itzik Leib was a tailor, a men’s tailor, and he made the most beautiful clothes for himself and for us, just marvelous clothes, and he was a very young man.

The girls, however, had only single names. The eldest was Esther, the next one was Eva, and then the next one was Rebecca, and then the last one who was born was Zlata. Zlata is not a Hebrew name, but it was probably a very common name.

My two sisters who came after me were seamstresses.

There was a great deal of self-help, everybody did the things, and my younger brother, he was really my buddy. You see, in a big family the children select their buddies. He was my buddy, I would take him by the hand and we’d take a walk into the qoyisher district to show him the gardens and the apple trees and so on. And we wandered around in this very quiet qoyisher neighborhood, we would hear a piano being played and so on, and we passed by a garden and there was a woman standing inside and she motioned to us to come over and she wanted to know — we understood a little Russian and she pointed to the trees — whether we’d come in and pick the apples, because we left for America in the fall. And we went there and I climbed on the tree and my kid brother was underneath with baskets, and we worked there for about an hour or more, they paid us a little money, I don’t know how much it was, probably a few kopeks. We filled a couple of baskets with the fruit and we brought them home.

The midwife and the children she helped to be born. Source: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Toys

You would ask, what children, young children did in Russia in those days? We played with toys. You couldn’t buy toys. We had to make them ourselves. Having a father like ours, who could improve on it, then you’re lucky.

My brother Chaim Pinchas was two years younger than me. We both made our own kites. My brother and I in the summer would get up very early in the morning, maybe five or six o’clock, and we knew where there was a little factory that used a lot of cord. I don’t know what they used it for, and they’d throw out the small pieces. And we’d go around there and pick up everything we could and piece them together, tie the knots together until we got a tremendous run of it. Paper was hard to get there. And for a kite you have to have strong paper, but we didn’t have newspapers even. And we would make the kite and we would cut the ribs that the kites need, tie the tail and we’d make it fly.

We couldn’t buy skates, though there was a lot of skating around and in winter our street, which wasn’t paved, became a place where you skate. My father would put a wire somehow around the shoe and we were able to go skating on those skates.

Even Hanukkah dreydlech we would make ourselves, we would melt the lead and pour it into a form.

Игра мальчиков во дворе хедер. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Schooling

Girls didn’t go to cheder. The boys had to, they had to know. So, we had a certain intellectual background.

I don’t remember the earliest time I was taken to cheder to learn, how old I was. They say at six years, but I must have been younger. I probably was five years old when my father wrapped me in his tallis, which was the custom. I remember the walk to cheder. I remember it as though it was today. You walked out of the house and you took a left turn and then turned left to the cheder.

I was looking forward to going to cheder. I was told you — you’re a man, it’s like Bar Mitzva. You become a man. And I guess perhaps they were preparing me from a very early age to look forward to going to cheder.

But I remember, I didn’t like the first cheder I had at all. I didn’t like the rabbi. He was dirty and I didn’t like him at all. He was nasty to the boys. He’d slap them on the hand with a cane and so on and so forth. As a matter fact, as a child of six, he made us read the Gemara.

Хедер. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

But later on, I went to Talmud Torah, which was a Jewish public school, a real school. That was taught in Yiddish. They taught us reading and writing all in Yiddish. It was run beautifully, very fine. We had to register every season, every semester, whatever it was called, and you’d get a ticket, and they’d assign you a class. The classes were very nice. We sat in a sort of an open square and the rabbi was in the middle there. The teaching was much different, they had very good teachers there. It was a real school. We learnt both religious and secular subjects. Jewish history, not religion and the three R’s, reading, writing and arithmetic like in the primary schools in America, the first things any person needs as introduction to culture. They also had sessions teaching Russian. That was part of that Talmud Torah. The Russian was evidently paid by the Talmud Torah, because I don’t believe that the government would pay for any Jewish school at all, I doubt it very much I remember the Russian teacher very well. He was not a Jew. He was a nice man with a small red beard. He was a lovely teacher; he knew how to teach children. He’d come about twice a week. Whatever few Russian words that I know even now, I learned from him.

In the school they also served you lunch. It was run by the Jewish community.

Талмуд-Тора, Ковель. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Reading

I read it even before cheder, because our home was a sort of a semi intellectual house for what we had. I remember once a young girl came to the house, I didn’t know her, she wasn’t a relative, she was a stranger. From my recollection now, she may have been fourteen or fifteen years old, and she said, “I understand that you can write.” I said, “Yes, I can.” She says, “Would you write a letter for me?” I said, “Yes, sure.” She told me what to write. I probably was by that time eight years old. I didn’t realize what it was until years later. It was a love letter she wrote to a boy.

There was common reading material for the Jews. We didn’t see a newspaper in Brest-Litovsk. I don’t remember seeing a newspaper at all. Maybe my brothers did. They always read, but I didn’t see a newspaper.

My father also would do some reading out loud. My father always read to my mother, while we kids would play. We had things to do, we would play on the floors. My father would read to my mother some stories. I still remember, “Dos Tepl” and various stories like that. I was always eager to see them printed. I used to read them, but of course they were a little above my age. I read Sholom Aleichem, Mendele Mokher Seforim and many others. I suppose, Peretz was already there. I mean those were the great lights, the big ones, and later on of course there were others.

Бейт Мидраш. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Language

The language, that I was raised in was Yiddish, absolutely Yiddish. That was an earthy language. Yiddish is a wonderful language. If you read Sholom Aleichem, you’ve got to read him in Yiddish, not in English. When I came to America I didn’t know any English at all. I knew a little Russian, and of course I found German quite easy, although I speak it a little. I used to go to the German theater, and I’d get every word because of its relation to Yiddish.

But my mother had a gut vortl, a good word for every incident. She would speak in Polish, in Russian and in peasant language. She said, “Der goy sacht,” and then she’d speak in that language always to the point. She would never tell a story, unless it was an appropriate story. I learned that from her. I learned that you must never tell a story, unless it’s appropriate, especially if it’s a little off-color joke.

It was common for adult Jews not to speak a word of Russian. Well, they just didn’t learn it. They could have done it. No one kept them from it, but just they didn’t want it. They were absorbed in other things. I don’t think they considered it not kosher or anything like that. Just a matter of not having the time for it.

Religion

My parents, while they were good Jews, they weren’t too religious. There was a liberalism in the home. My father read a great deal when he was able to rest from his hard work.

I remember the synagogue very well. It was like a big temple really with a high ceiling and I always wondered how they get up to the lights up there, never realizing they pulled them down.

On the big holidays the place was filled. Father would bring me and my brothers to the synagogue, but not sisters. The women didn’t go except on the big holidays. Of course, they went upstairs or in the back, wherever it was. But I always went with him went on Shabbos Friday night and Saturday morning.

Sometimes I was bored, but in the main it was all right, and the reading of the Torah and everything else, it was very exciting. The ritual is very, very attractive.

Редкий кадр интерьера Большой синагоги. Источник:

When it got noisy the shammes would clap his hand on the big book, till it was quiet, and it reminded me of home really years later, that’s universal.

On Saturday afternoon after the dinner and after the nap, we’d go to the synagogue and there was always what they called a redner, speaker, and generally they were very glib speakers, spoke very well, and they told anecdotes about what happens to Jews here and there and they’d quote the Bible and they’d quote the prophets and so on, and they’d make a collection, that was his occupation. And I don’t want to mix that up, but it’s very possible that Jesus Christ was that kind of a man, because he always lectured, always talked to people and so on.

Oyrech auf Shabbes means a stranger for the Sabbath. Bringing a stranger home to your Friday night meal was common. I have an idea that there were many shnorrers who took advantage of it, but you couldn’t help that. But in the main they were people who were very quiet. Some men talked a lot. I suppose they were just businessmen, travelers. There are a lot of stories about those people.

There were many Hasidim in Brest-Litovsk.

Not far from where we lived, they had what they called a Hasidic shtibl. It wasn’t called a synagogue. It was a house, a Hasidic house. And as kids we would stand in the doorway of those places and watch their curious antics, and we all looked down on them, all the Mitnaggedim looked down on the Hasidim.

There was no interaction between the two kinds of Jews. I suppose just the fact that one thought that they were superior to the others, but I never saw any. We didn’t have friends among the Hasidim at all.

My parents talked about Hasidim that they are too obsessed by their religion. Also, a curious fact was that Hasidim were too happy. They were merry. They sang and they danced and so on. The average Jew didn’t dance.

Разносчик мацы. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

Diet

It was a kosher home, absolutely a kosher home. We bought kosher meat absolutely. My mother would go to the rabbi if she found a blutzdroppen in the egg or in the chicken. If it wasn’t kosher, she would have thrown it out. We never ate meat during the week, only on the Sabbath.

Our diet was excellent, although only on the Sabbath we had chicken or any kind of meat. I attribute my long life to the diet that I had, when I was young.

The diet during the week was a plentiful diet, although you didn’t get any meat during the week. You might get rather what they call the chitterlings. The chitterlings are what the blacks call soul food, which consists of liver. Liver was very cheap and, as a matter of fact, when you bought meat, they’d give you the liver for nothing. And then there was gefilte kishka. You know, my mother would stuff this, the derma, put wonderful things into it.

We always had marvelous soup, thick soup, be it with a nice marrow bone. We used to have soup every day. As a matter of fact, one of the meals was cold soup. It was very fine, a mixture of barley, beans, peas and carrots.

The food was generally better then. Practically all fresh food, except in winter we didn’t have the fresh food, but we had the carrots that were always good. My mother would buy in summer cucumbers counted what was called in Russia shuck, sixty cucumbers in a shuck. It was the measurement that the peasants would come with their wagons, and they would sell cucumbers to whoever wanted to buy them. My mother would pickle them herself. I can assure you it was really a delight to eat. When we left for America, my mother took along a small barrel of these cucumbers, although we could have bought them on the ship later, when we ran out, because we went on a German ship and they had plenty.

My mother was one of the most wonderful bakers. She would make a challa about two and a half feet long. It was a big family. She’d make always two, always two, because Friday night when Father came home from the synagogue he would sit at the head of the table, and I remember often my mother forgot to put a knife down there for him to cut it and he couldn‘t speak. After he made the broche, he could. Then in Yiddish he’d speak, “Messer”.

Preparing for the Sabbath was really an event. The house was cleaned up beautifully, a white tablecloth on the table, my mother would bentsh licht, and it was an event, the ritual was very fine. And then we would all sit around the big table — we had a big table — and my father would make a broche by the bread there and he would cut slices for each member of the family and then we’d all eat. We had chicken and all sorts of tsimmes. My mother was a very good cook, and it was very pleasant.

The Passover was a terrific, big holiday, and you really had to scour the place, really clean up the house, burn all the chometz with prayers.

You couldn’t buy matzoth in boxes or packages, you had to make it, so what they did was to organize a little cooperative play of fifteen families and they hired a real bakery. The baker would clean the place up, so that there was no breadcrumbs in the oven, you see, and it was arranged in this way. Suppose there were ten cooperators. Each one would be assigned a day when their matzoth would be baked, and everybody in the cooperative, all the women in the cooperative would work for this member, roll the matzoth and so on, and there was one boy who would sit on a table — that was myself — to put a measure of flour into a bowl, big bowl, and my brother, who was two years younger, he must have been four by that time, he would put in water. That was assigned, exactly a measure of this, then a measure of that. You don’t put salt into it, I mean just water, a little water and flour, that’s all.

Then there were two women who would knead the dough. There were tables, long tables that were covered with a clean metal, so that the matzoth didn’t touch the wood because the baker used to use it for his bread.

And when the dough was brought onto these tables the cooperators, the women, would stand there with rolling pins and roll them, and the matzoth were always round, because you can’t roll square matzoth. Then the man would come around with something that scraped the top of it so it wouldn’t rise, making little holes in them with a little role that had points on the bottom. So it will not rise when it was baked. And then it was taken to the oven on a long shovel, so to speak, full of butter, and he put it in the oven, and when it was through the woman would provide a basket and it was done for the day. This was done for every member of that little cooperative.

Выпечка мацы. Источник: Photographing the Jewish Nation Pictures from S. An-sky’s Ethnographic Expeditions.

On a smaller scale there was another cooperative and that was preparing the hot food for the Sabbath. You’re not allowed to cook or light a match or anything on the Sabbath. So, our apartment was fixed with a very big oven, very deep and so on, and my mother made it a sort of a headquarters of the women in the little commune that we were in. There must have been about ten of them. They brought their food on Friday afternoon. It was all closed up in earthenware pots generally, they had their dinner for the next day. And my mother would heat up the oven with wood and than clean it out with a brush or something, and that was put in Friday afternoon and then the oven was sealed and it stayed overnight that way until the next morning, next day, and just before the men came back from synagogue they would come and get that. My mother would take the pots out and put them on the floor and each woman would identify their own pot. They also left a little coin for the wood that was used. There was no charge, but this was a custom. My mother didn’t accept any pay, like the baker, who was a professional. Well, the opening of that pot, it really was the most pleasant smell. They put the finest things into it, and it was real hot. I can never forget it.

Political Atmosphere

I remember not very much the political atmosphere at the time I was growing up, but there was talk about it.

My eldest brother Hersch Yudel, who I remember extremely well, was an ardent Zionist from the time he was able to say the words Zion and Zionist. In America in his room he always had a picture of Theodor Herzl, this very handsome man standing in front of a rail of something. My brother belonged to a group of young boys and girls who were Zionists. In fact, later on when we were in America, he and I never got along because I was a Socialist and he was a Zionist. Being older than me, he sort of kidded me all the time about it.

My second brother, Louie we called him Itzik Leib, belonged to the Bund. He was a revolutionist, he was about, I think, sixteen or seventeen when he joined the Bund, the Yunge Bund, which was the Social Democratic Party, the Jewish branch of it. And my mother told him that she’s getting worried about him because he was getting to be outspoken. He was a sort of a firebrand anyway. So, he stood up on the table and yelled out loud, “Tsar! Down with the Tsar!” Well, my mother just nearly died. Fortunately, no one heard this, it was indoors, and this is the kind of a guy he was. We did hear of arrests and so on.

Фрагмент карты Брест-Литовска с жилыми кварталами и интендантским городком.

Army

There was an armory next to our house. The soldiers made a tremendous impression on me and also on the other young boys of my age that I associated with. They were so close to us and their big yard wasn’t big enough to drill, so they’d go out into the street. They didn’t have music, but they had a drum of course in order to keep the rhythm, and they would march up and down the street, drill there and the kids, four or five of us, would always follow them and the soldiers liked that. We would follow them, drilling the same way they did.

And when ration day came around, they were given their rations. It would come in a truck. They would get their rations for the week, I think. Bread, for instance. They got a big round loaf of bread. And when they got the rations, they would come out and sell part of it to the natives seven kopeks a loaf. It was the most delicious bread, all black bread. It was black, but it was wonderful. I still remember the taste of it.

And what they did with the money was to go out on the town, buy themselves a little vodka and buy these sunflower seeds and they would eat the inside and they’d spit out the shell. The streets generally were filled with those seeds, with those shells. This was a habit of theirs. Not only of theirs, but most of the Russians would do that.

And also they had parties in the barracks and they would invite people to come in. And there they had music, they had these accordions. They were marvelous accordion-players, all of them.

In the Russian Army — I imagine it works the same way like in most armies, no native boys stay in the city where they were born. They send them far away and they bring faraway people to our city, so we never knew them, and I think it’s done deliberately, they’re always afraid of riots or revolutions or so on, that sort of thing.

My eldest brother, who was called for service must have been eighteen or nineteen years old, and of course he didn’t want to go. So, he did what most of the Jewish boys did there, they underfed themselves and did not sleep for a month before they were called to report. And he and a friend of his were called together and they wouldn’t allow each other to sleep more than two hours, one was awake and the other was asleep. If he slept more than two hours, he’d wake him up. And they didn’t eat much, they actually starved themselves. So, my brother and this other fellow were completely underweight and groggy, so they were not taken. It was widespread among the Jews.

The man who lived in the dark room of our apartment, he was drafted. Though they sent him away, far, far away, he came home on leave, and he looked marvelous, he looked better than he ever looked. He was well fed, he said. And when he was through with the army, he came home. Once he was sitting on the stoop of a house near the armory, and an officer came by, he was already in civilian clothes, this young man. And when the officer came by — I was there when it happened — he stood up and saluted, because he still thought he was in the army. His family moved soon after he came from the army and I never saw him again.

Washing in the Bug River

You wonder what was done about getting clothes clean, when there was no water in the house. Well, Brest-Litovsk had one of the finest rivers, the Bug River, which was quite a wide river. And once a week, or maybe once every two weeks, my mother joined many of the other women and went to the river to wash their clothes. They would put the clothes into river water. When they were wet, the women would pound them on a rock or on something flat. And the only other place I ever saw this done, on a much bigger scale than on the Bug River, was in India. In Bombay I saw hundreds of men and woman do this, the same thing to their laundry on rocks that my mother used to do and many other women did in Russia and it reminded me of home.

When the women came home, those clothes were clean and had to be ironed. Of course, the ironing was done at home. It was more work. The women all worked all the time.

Водовозы набирают воду в реке Мухавец в Брест-Литовске.

Travel to America

My father came to America first and this is an interesting story. My father had a co-worker in Brest-Litovsk, Zbunchik was his name. He was about the same age as my father. He was kind of a homely man, but he was a marvelous guy, good-natured and wonderful. Being a bachelor, he saved up some money and he was the one that put the idea of going to America to my father

People went to visit America and came back showing how well-dressed they are, painting such a glorious story of America. We also had letters from our friends in America. The impression they created was one of prosperity. In fact, the slogan was that money grows on the sidewalks. Streets are paved with gold. They said money, you’ll find money. Well, you could find money, but how much money could you find? Well, Zbunchik staked my father and they left Russia together. Of course they had no reason to be held back because they weren’t of military age anymore, but still to leave Russia was a trick. You had to get across the border by paying somebody something.

My father stayed in America a year and saved up a little money, probably lived in very bad quarters, I don’t know where they were.

We got very lovely letters from him, encouraging, saying that he was able to find work. My mother didn’t rely on crossing from one country to another on luck the way most of the immigrants had to go through, in Germany or in Poland or so on. She went right to the authorities in Grodno. Grodno was the capital of this particular gubernia where Brest-Litovsk was a city. And she took my sister along and she left the other children with neighbors and she went to Grodno, to the capital. She came back with a passport for all of us, one passport. She reduced the age of all the children, although she didn’t have to, but she wasn’t sure, if she may have to pay full fare for me and so on. My greatest loss in life is that I don’t know what happened to that passport, it was really a gem.

Before we left for America, my mother sent us to the barber to get a haircut because we were leaving in about two weeks or a week, to look good when we come to America. We went to the barber and he really clipped us. I mean, payess were taken off and everything.

We crossed the grenetzwhich is the border on a railroad train, which was just perfect. The train stopped at a town in Prussia. We were isolated for a couple of days there and then we had to go through fumigation process where they fumigated all our clothes and they examined us naked and we all passed anyway. On the day we had to leave, we had to pick up our clothes on the other side of a fence. They were quite warm yet. From there we took a train to Berlin. We stayed overnight in Berlin and the next morning we took a train to Hamburg and from there we took the ship to America.

Иммигранты на Атлантическом лайнере «S. S. Patricia»